Keeping water safe – or just keeping it

The big challenge is not at our local reservoirs.

I had to break ice on the pond this morning. I held the thermometer under for 30 seconds (2° C), then pushed up my sleeves to dunk three sampling bottles deep in the icy water.

I’m among a handful of Citizen Scientist volunteers, overseen by a local college professor. We’re worried about growing pollution from diesel soot, business waste, and domestic leaching. We live on a populous island whose watershed is small and fragile.

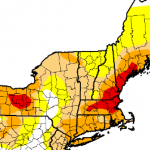

But local challenges are nothing compared to the country as a whole. There appear to be huge potential costs ahead in protecting America’s endangered fresh water.

The Ogallala aquifer (video left), a giant underground reservoir under six plains states, provides water for 20% of America’s farmland. Its recharge rate is negligible, and we are depleting it rapidly.

Thirty million people depend directly on the Colorado River (video below), and Southern California’s Imperial Valley produces about 80 percent of the nation’s winter vegetables. Studies say odds on the Colorado, and the homes that depend on it, running dry in any summer will soon be even money.

Protecting local water supplies, like my modest efforts, can help make sure our grandkids have clean drinking water. But we can’t make sure they have food, much of which comes from the Colorado and Ogallala.

It’s going to be tough, maybe divisive, but the country can adapt to this.

We can all fight climate change. But the weapons to fight drought are mostly in the hands of a dozen western and plains state legislatures. Any idea how we can help them deal with this threat?

[See a subsequent post with some answers.]